Memories of Irene Rogler Palenske

Going Home

At last the announcement! “Last call for Number 9. Leaving at 10:00 o’clock. Gate 2. Passengers loading at Gate 2.” I followed the redcap. I am going home. The great diesel sighed patiently, haughtily unaware of the scurrying humanity and rolling carts of luggage. We found my seat on the coach and the redcap waited with professional ease while I dug for his tip. I sat down and cupped my hands against the glass and looked out into the yards.

Ribbons of track parallel our own stretching straight into the darkness but I remember how they soon fan out across the country to where the big trains will take others to their homes, or away from them. The station with its impersonal music, hub-bub of voices, littered floor and hard backed seats is soon left behind. The train in contrast is personal and warm. It is my train. It is taking me home.

Home means different things to different people but wherever or whatever it is no one can take it away, for memories have their permanent dwelling place there. Just as a motion picture that is run backwards, no matter where life takes us or which pair of tracks our train of thought follows, it leads back eventually to that dwelling place where memories were born.

My memories are good memories for I have a good home. Love has always existed there; love, respect and consideration for one another – for the casual visitor – and for the old friend alike.

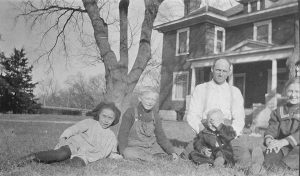

Number 9 is moving now smoothly, slowly, softly lighted – a hum. I like that hum. It is the melody of voices blended above the rhythm and the rumble of the great wheels against the steel ribbons that lead toward home. I lean back and close my eyes and I see our big white house with its expanse of lawn and big trees surrounded by the low friendly wall stacked stone on stone by grand-father so long ago.

The conductor asks for my ticket and tucks a punched slip into a slot above my seat. To him it says Emporia. To me it means a smiling welcome from my family who will be there at the station to meet me and take me the rest of the way home.

Confident of that welcome I lose myself in reverie. Memories flood my mind even as the first spring rains flood our valley every year. Little pieces of my youth slip by bobbing here and there with no chronological order. Some are fleeting and are gone. Others ride the crest of the wave – and yet each has added to my life. Who was it said “You are your own best memories?”

For no reason I suddenly smell a freshly cut alfalfa field and feel the rasp of grasshoppers hitting against my legs as I walk in the stubble there. I remember following a turkey hen to her stolen nest among the grass and rocks on our side hill. I gather Easter lilies for my Mother on her birthday, the very next day after I had found my new baby brother tucked on a big pillow in the old willow chair next to her bed. I was only five then – so long ago it was.

I hear the low of a cow for her calf and the coo of the pigeons in the loft. My ears tingle with the sound of crickets and locusts on a hot summer night as I try desperately to sleep in my stifling upstairs bedroom.

Home. I’m going home where no longer can I hold baby chickens in my cupped hands and press their soft chirping bodies to my face, but I feel them all the same. I’m proud as I remember the size of my hand when I can hold three white eggs at once as I gather them from the hen house – or from stolen nests, the ones way back in the hay loft or under the horse’s feed troughs – my old cat jumps on my shoulder as I walk by and rubs her head against my cheek.

The hay loft! A haven for secrets and for stealing sparrows eggs and for stories told by my cousin “Windy” as we sat in the cupola before we drop from the rafters into the new mown hay, dusty, scratchy, and buoyant – then scramble back up the ladder to jump again.

My children have never known the feeling of liberation and exhilaration when it was time to leave off long underwear in those first warm days of spring. Ah, spring in Kansas! When after eight months of country school we celebrated the last day with a school picnic in the woods near the creek, there to play games and wade, and pick Johnny-Jump-Ups and dandelions. It was spring when I could find violets along the stone fence near the south Cottonwood tree. It was spring when I could hear the coyotes howling in concert from the hills and when I could feast my soul in day time with the sight of those same rolling hills now green again and dotted with wildflowers and white faced calves.

It meant watching the hired men making straight deep furrows behind the team of horses and we knew that soon little green corn plants would cover that rich brown earth.

Indian arrow heads hung from a board on the barn wall; arrows that had turned up with the plows and had been painstakingly chipped from flint rocks that had broken from the ridges along this range of Flint Hills, so beautiful and unique to this part of Kansas. It was kind of sad thinking of the Indian who had to leave their homes so long ago but we pretended in fall that the corn shocks were tepees and that maybe their spirits returned then, who knows?

I suddenly remember helping Mama brush flies from the inside of the house with branches from the elderberry bushes and hear her scold that it is high time to get the cattle out of the near by feed lot and out to pasture. Then I can smell the cattle pens again and feel a little sick. But that memory is soon replaced with the scent of June roses at the Children’s day program at our little church and that was the loveliest day of all.Thinking of smells how can I ever forget that blended aroma of egg salad sandwiches, bananas and chocolate cake I found in my daily dinner pail at country school?And thinking of school I’m off on another tangent of nostalgia. There were the big boys, who were nice to me and the little boys whom I ignored, and the girls that snickered with me in the closet. There were the taunts of “Teachers Pet ’cause your dad’s on the school board,” when I won the spell down and the sympathy of the same classmates when my older sister and brother, Helen and Wayne were no longer there to tell my folks the naughty things I did. There were the exciting box and pie suppers with fancy boxes that Helen and I made – and there was once the awful humiliation when daddy the evenings auctioneer, bought my pie because it was leaking through it’s crepe paper wrapper. I had to eat it with a spoon with a boy two years younger and I hated him and my dad.

One time the school used the money from the box supper to buy a gramophone – It was kind of a big box with a horn and the music came from a blue celluloid looking tube, like a can with both ends out of it. We bought six of the records and they were absolutely wonderful. The needle was a real diamond chip and would never wear out. It cost $18.00 altogether, and that was a lot of money but after all it had that diamond needle and it was worth it, Gosh!

The taste of new peas and little round potatoes creamed together and served with the first fried chicken and roasting ears lingers in my memory like a benediction. And homemade ice cream! No gourmet chef can ever match that.

It took one of us kids to sit on the gunny sack on top of the salty ice to hold the freezer down while daddy gave it the final turns. When it started to jump off the floor, kind of, and the handle just wouldn’t go around again the ice cream was “done.” Off came the sack and then the ice from on top of the lid. Next the lid was removed with extreme caution, so no dirty salt water would creep over the edge and spoil that smooth, creamy, vanilla flavor. A shout to mama brought her with her spatula to do her part. By careful scraping and pilling at the same time the floppy ladle would come free still thick with ice cream. We kids all jumped around and begged her to leave just a little more than last time on the ladle and then whose ever turns it was, was handed the prize. On a hot day one had to lick fast and lean away over because little gobs of the good stuff would slide off onto one’s clothes. It was hard to reach the center part of the ladle with one’s tongue and the cream always got all over one’s face but that was small price to pay for such a treat.

Now the hole in the lid was plugged up with waxed paper and clean crushed ice put on top of the can, and an old rug on top of that so the ice cream could really get hard before dinner. Then it was served in oatmeal dishes with big pieces of cake.

The Sunday cake, and a lot of other food for that matter, was a necessity. They were prepared with the experienced expectancy of a houseful of hungry relatives or friends or both, before that day would be over. If they arrived before noon we sat at the big dining room table for mama's hot fried chicken, mashed potatoes and cream gravy dinner.

At dinner my uncle who is visiting asks if the ice was good last winter and we all talk about how thick it was on the creek and how hard it was to get it cut and hauled to the icehouse and packed between layers of sawdust on such cold days. Then we all laugh for it doesn’t seem right now that it had ever been cold outside, even though the big chunks of sawdust covered ice that daddy brought in this morning proved that it was.

Saturday was churning day and I liked to see the little drops of butter milk ooze out on top of the yellow butter as mama worked it in the big wooden bowl with a curved wooden paddle. Then it was my job to use the same wooden bowl to cream the sugar and butter for the Sunday cake. The inevitable Sunday cake.

The Sunday cake, and a lot of other food for that matter, was a necessity. They were prepared with the experienced expectancy of a houseful of hungry relatives or friends or both, before that day would be over. If they arrived before noon we sat at the big dining room table for mama’s hot fried chicken, mashed potatoes and cream gravy dinner. If they arrived in the afternoon they “had to stay” for a paper plate supper of cold fried chicken and sandwiches which we generally ate on the front porch complete with flies and good fellowship.

The only trouble was the awful lot of dishes that had to be done. The women always shared in doing them and we girls were expected to help. I generally decided I wouldn’t be missed after a little while, by anyone besides my sister, anyway, so I’d just disappear. Cousins were very helpful in this for they didn’t like the dishes either.

Sometimes the cousins came to stay for a week or two and we played barefoot in the grass and weeds by day and counted our chigger bites by night to see who had the most.

My older sister, Helen didn’t like me much because I worked harder when relatives were around than when they weren’t, to win their praise, and my older brother Wayne didn’t like me much for I followed him and his friends and I didn’t like my younger brother, George much for he followed me and my friends. I didn’t even like him much when I was in high school and he sat around and grinned when I had a date, and I didn’t like mama much then either for she thought he was funny and wouldn’t make him go to bed. But like and love are different. We all loved each other then as now.

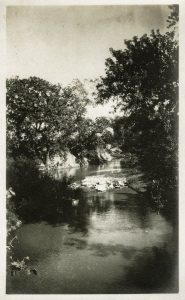

The cool of the swimming hole and the smooth feel of its slate bottom with its covering of slippery mud, after walking in bare feet over rough gravel was the best part of summer. We all learned to swim under Mamas’ firm hand and we learned to expect a laugh from daddy who could stand on his head in the water with his feet straight up in the air. Dragon flies flitted above our Willow tree houses where we dressed and We felt as lazy and as much a part of nature as they. But oh dear Goddess of Memory! Don’t remind me even now of leaches. I can’t bear the thought of one of those black blurbs fastened between my toes.

In winter the same high banked stream became the starting place for our mile long skating rink. No one has really lived who hasn’t experienced the thrill of ice popping thirty yards ahead of his skates but not really breaking through, then going home with the gang for cocoa around a roaring fireplace fire.

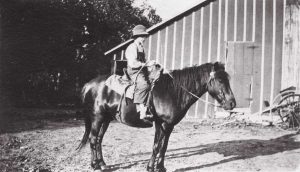

I can feel the sting of the wind on my face as my old pony, Pearl, takes the bit in her teeth and runs for home after being tied up all day in the shed on the high school grounds. I chuckle with the wonder of the response of our old Model T motor as I crank it to drive that mile and a half to school after I’ve out grown old Pearl for transportation.

Someone persuades daddy to play his fiddle and he sits with eyes closed and foot tapping as his nimble fingers play “After the Ball is Over,” and “The Irish Wash Woman” and an endless number of square dance tunes – Sounds of my youth! – George with his banjo and a dozen verses of “It Ain’t gonna rain no more,” Helen at the piano as we all sing together – music lessons and practice for me – and who can ever forget Wayne singing loudly and off key as he brings in the cows astride old Jack, his Shetland pony.

I see Mama sloshing in “gum boots” as she lugs Mash to the chickens, or carries in an armful of garden vegetables to wash with the hose. I see her proud and happy face when she can at last pick a big bouquet of red zinnias from her well tended flower bed in the corner of the yard.

Butchering time and canning time – work, work always work but daddy whistled as he worked and mama didn’t complain. I learned that people do what they must do and cheerfully.

In my drowsy mind I dream I smell bacon frying at dawn and I listen for the clink of the iron lid as Mama puts more wood into the firebox of the big old cozy range to finish breakfast. Only then do I crawl out of the warm covers and run down stairs to dress by the open oven door.

Today is wash day and we kids will take turns pushing the handle back and forth on the old wooden washing machine but it’s really Wayne’s job. He gets 10 whole cents for every hour he works.

I am proud though for we have running water in our house. Even the cistern water can be pumped to the storage tank on top of the hill for our guarded use and that is really something special. I liked it best when daddy took the big cover off the cistern to gauge the water depth. Then we kids would holler “Hello, down there” and the echo came back big and hollow and exciting. If daddy held on to us we could look down one at a time to see our faces mirrored in the black depths below, but generally bugs floated about to spoil the image.

Once or twice a day one of us kids was sent out for a fresh bucket of water. Sometimes you’d pump and pump and nothing would happen so you’d have to go get a cupful of water and pour it down inside the pump to prime it. Then you’d slowly lift the handle up and down and pretty soon the water would start running from the spout. That never made sense to me but that’s the way it was.

We didn’t dare drink the water from the faucets tho. It tasted awful after standing in the reservoir in the sun so long and besides it must have had germs in it coming through the pipes so far. The water from the well, north of the house was cold and pure tho and daddy always bragged that it was the best tasting water anywhere in the county. Then he’d laugh and say the reason it was so cold was because it came from the north east corner of the well. He had a lot of little jokes like that.

Once or twice a day one of us kids was sent out for a fresh bucket of water. Sometimes you’d pump and pump and nothing would happen so you’d have to go get a cupful of water and pour it down inside the pump to prime it. Then you’d slowly lift the handle up and down and pretty soon the water would start running from the spout. That never made sense to me but that’s the way it was.

You threw away part of the first bucket full to be sure that the water you took into the house hadn’t stood in the iron pipes. Then you carried the heavy bucket into the kitchen and put it on the corner of the cabinet. A tin dipper hung on the wall beside it and invited anyone who came by to quench his thirst. We didn’t worry about germs when just the family was there, but I remember visitors were always given a clean glass from the china closet. They seemed to like it better that way.

I did kind of think of germs tho when I took a drink from the tin cup that the hired men all drank from. It hung from a wire on the windmill which pumped the water for the horses. Mama said the cup was surely well sterilized by the blazing sun. I guess the cup didn’t interest me much anyway for I had a better way to get drink. I would pump real fast, until the water started running into the pipe that hung over the spout and sloped to the horse tank. Then I’d run to the end of the pipe and try to catch the cool water in my mouth before it all ran into the tank. Once I got some green moss that was floating there in my hair when I had my head upside down like that so then I used the boys method of holding my hand over the pipe and letting the water ooze out just fast enough to drink. It wasn’t as exciting a game that way – but it certainly was better than using that rusty tin cup.

I smile to myself as I think of hearing my son talking to his boy friends about what could happen on a rocket ship if it blew up in space. But that was sheer conjecture compared to the dire things Mama predicted for our house if daddy ever forgot to put the cap back on the carbide tank after he had added the grey lumps of carbide to the water to make the gas to light our house. Once he did forget too, and Mama said if anyone had lit a match down there in the basement our house would have been blown to bits. It smelled bad enough. I suspect she was right.

Across the room from the carbide gas tanks sat our enormous old grey safe. It represented absolute security from any kind of loss – for no robber, or fire or even a cyclone could force its way thru its thick walls. Only one person could open it, my dad. He kept the intricate combination in his head and on those rare occasions when he opened it we kids were his admiring audience. The little dial could go just so far one way and back so far another or else he had to start all over again. But he’d know just when the last click sounded perfect and then he’d stand up, give a hard jerk on the handle and the thick heavy doors would swing wide to reveal the rather small and dark interior smelling slightly musty. Each of us kids had a little drawer where we kept our most precious possessions. In mine I kept the first five silver dollar I’d ever earned and a shiney $2.50 gold piece I had received for Christmas one year. It wasn’t any bigger than a penny. How could that be possible?

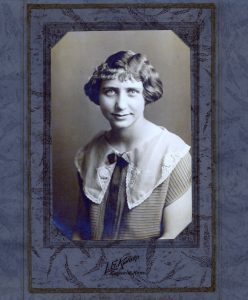

On the other side of the safe there were some important papers about the ownership of the land and on top of those a box of pictures. It was the pictures we waited each time to look at and talk about for mostly they were pictures of Mama and daddy taken on their wedding day. Daddy was slender and young looking with lots of hair and a nice smile. Mama had on a white dress with a tight waist and a high collar edged with lace, and big full sleeves and some roses sewed to the shirt. She had an impish smile on her round face and real puffy hair and I hoped I’d look that pretty on my wedding day. There was one picture too of Mama holding my brother Wayne, when he was a baby and she told us once she had it taken because Wayne was sick and they were afraid they might lose him. We always speculated on what it would be like without Wayne in the family but the idea wasn’t very real and seemed more funny than sad.

The tin types were the best, especially the one of grandmother holding daddy on her lap when he was just a tiny little baby. He had on such a long dress it went clear to the floor and looked almost like a part of her skirt.

Finally daddy would get tired of our “mussing things up” as he called it and then we’d put things all back like they were and the doors would bang shut for another six months of serene and smug protection for our valuables.

It was the custom to burn the dead grass in the pastures in very early spring so the little new tender grass would get a better start and be more available to the cattle. What a gorgeous sight it was to see the licking flames against the black sky at night – and the smell if you weren’t too close to it was indescribably pleasant. But sometimes the fires got out of hand if the wind came up and a farm house or barn was threatened to be saved in the nick of time by courageous cowboys and farmers.

Then the gentle rains fell, and the black gave way to patches of green and then it was that the cattle drives began. First I’d hear the thunderous sound of hooves on the dirt road by our house and the familiar “yup, yup, get along there” sing song of the cowboys who herded them toward the pastures south of us that were to be their homes for a few months until they were ready for market. Sometimes the herd was made up of long horned, skinny, tough old steers half crazed for lack of food and were looking for trouble. They’d been shipped from Texas or New Mexico to a town ten miles away and now were being driven to their assigned destination. Sometimes the men used bad words when a long horn broke ranks – and I laughed secretly and said the words out loud so I wouldn’t forget to repeat them to the girls at school.

Cattle drives were before the railroad was built across the road from our place and literally torn from the side of Pioneer Bluffs, lovely Pioneer Bluffs that grandfather had named over a hundred years ago.The grade was 65 feet above the road but the tops of the bluffs soared haughtily above it ignoring but rather proud of their wound, I think.

First the engineers came and surveyed, followed by blasting and the donkey engines and dump carts to make the fills. Workmen of all kinds came and brought the outside world to our very door. They lived in shacks and tents and they built the tressles and road bed. They also made the Saturday nite dances over the grocery store a good deal more exciting than they had been before, but Mama and Daddy kept an eye on us there. Oh, yes, indeed!

The unforgettable sight of twenty black men stripped to the waist and swinging huge sledge hammers in rhythm as they drove the big spikes into the railroad ties, will live in my mind forever. And then there was our friend, Mr. Applegate, one of the contractors and his wife from Montana and Washington who lived at our house for two years. They added much to our lives. They even persuaded Mama to permit me to date Joe from Georgia a little bit. Joe who called me his “Georgia peach” in his thrilling southern accent and whom I loved dearly altho I didn’t dare admit that for I was only sixteen and he was twenty five. Yes, the building of the railroad, so greatly needed by farmers, ranchers and housewives alike brings such a flood of memories I dare not dwell upon them or I’ll be dreaming far into the night.

I wonder idly just how far we have come for it seems much of my little girls days have passed thru my mind and yet more memories came and won’t be denied their place in the rushing stream. I’ve thought of helping Mama and Helen cook for 15 or 20 threshers or silo fillers when there were too many of them to send them all to the boarding house at noon time during those busy times.

I’ve watched fascinated at the big steel drill working up and down held in place and dropped from the huge wooden oil derrick as the oil drillers brought in the salt water well in the field across the creek. (Actually daddy was relieved he said for oil would spoil this beautiful valley – and he meant it.)

I’ve sneaked with the other kids close to the campsite of gypsies who came to camp over night near Cracker Creek bridge near our house. We were mystified by their strange language and thrilled to their plaintive music as they sat around the fire near their old “mover” wagons and skinny horses tethered in the lush grass. Daddy said they stole roasting ears from his field along the road but he didn’t believe they would steal one of us kids. But we believed it and were glad to watch them from the dark, ready to run at any suspicious move.

I marvel even now, at daddy’s skill in making a real whistle from a slippery elm branch and I remember how it felt to sit in the crotch of an apple tree eating a sweet Maiden Blush apple and knowing the world was all mine. Nothing would ever be impossible – but then I wasn’t wishing for much. I was too contented for that.

Our first car was a big black elegant Chalmers but whenever we went anywhere Mama was afraid someone would hit his head on the wooden cross bar that held up the top above the back seat. We always ducked and sat with our heads in our laps when we saw rocks in the road. Daddy said it was pretty hard to miss all of them but someday he’d bet we’d have roads smooth as anything, now that more people were buying cars. But even Mama had to admit the Chalmers was better than riding in that old surrey behind horses. About all I can remember about the surrey is how high it was from the ground and how hard it was to sit on the narrow slippery seats for very long – but the jingle of the horses harness was nice and the black whip to use on the horses looked important. Not that anyone ever used it.

I was nine when the war started and I could read all the awful stories about spies and the Kaiser and I was scared daddy might have to go too. But the big day came when we could hear the church bells clear down to our house and we knew the war was over. That night we went to town where the men built a big bon fire and we kids played and threw on more sticks while the mothers talked about when the boys would all come home again. There will never be anymore war the men said – No country would ever dare start another one they said. It was a happy day. It was a happy day too when years later daddy brought home a new thing called a radio. Music came out of the ear phones that you put on like a telephone operator. Daddy was so excited that he called up the neighbors and let them listen when he put the head phone to the mouth piece. It was quite a while before we got a set in a cabinet that everyone could hear at once.

Violent wind storms that could flatten the wheat in one breath or gentle breezes that could make it into a beautiful rolling yellow green sea, that was Kansas. Devastating floods or hot blistering sun for days on end could prolong the cruel drought that was in its seventh year already. That was Kansas, too, or really Pioneer Bluffs for they were one and the same to me.

Violent wind storms that could flatten the wheat in one breath or gentle breezes that could make it into a beautiful rolling yellow green sea, that was Kansas. Devastating floods or hot blistering sun for days on end could prolong the cruel drought that was in its seventh year already. That was Kansas, too, or really Pioneer Bluffs for they were one and the same to me.

Pioneer Bluffs, the name of our farm, where I grew up and finally went off to college to return at vacation times with a house full of friends for whom mama heaped the table and sent back to school each with a box of cookies for his own. It was on one of these vacations I put on my beloved’s fraternity pin and it was a year after college that I was married to him in front of the fireplace banked with garden flowers one hot July day so long ago. Pioneer Bluffs, where we took our three children every summer and they too caught lightning bugs and put them in jars and marvelled, only to let them die forgotten – There they too fished for “pumkin seeds” in the creek and put them in the slippery horse tank and tried to catch them later without success with their hands – but somehow the little fish appeared all brown and crisp on grandmother’s breakfast table the next morning – They learned that the only relief for nettle sting was cool mud – and they heard their grandpa’s old jokes and riddles and there I was living it all over again. This is my heritage and theirs.

I adjust my pillow and curl up in my seat and only then do I notice the hum of voices is no longer audible. The lights of the car are off now and I am ready too, to rest but one thought persists. It keeps coming back to me as it has so often throughout the years and my heart is filled with gratefulness.

The thought is about my grandfather Rogler who came alone as a boy of only seventeen all the way from Germany to stake his claim in this fertile valley. Over a hundred years ago that was – when only a few other courageous men were there to build their homes and somehow make the land yield a living for them and their families. From that home founded by my grandfather and grandmother, an American girl who came to share his dream, generation after generation has spread out to the distant shores of America and beyond. It is almost as though God had dropped a pebble into the pool of life and the little concentric waves that radiated from it have never stopped. Life is made up of little things and memories give them their only permanence.

The past – the present. They seem the same to me now. They blend to make my life’s stream. I lie back contented thinking of the members of the family I have left for a little while and of the ones I am going to see in the morning. I whisper “goodnight” to them all and drift off to sleep to the music of my train.